Background

Since taking office, President Donald Trump imposed and signaled a bevy of tariffs on various trading partners of the United States. These tariffs seek to counteract growing federal trade deficits and rejuvenate the American manufacturing sector by levying a tax against imports. The government designed each tariff to insulate a particular industry from foreign competition, advance a policy goal, or serve as a bargaining chip in trade negotiations. As such, tariffs continue to be a hot button issue in the global economic conversation. Some economists maintain that tariffs usher in increased prices, inflation, and a decrease in innovation due to lack of foreign competition, while some politicians assert that tariffs will bolster manufacturing and reduce dependence on foreign trade. In this article, Forvis Mazars investigates these assertions by exploring the impact of tariffs on innovation and examining the Credit for Increasing Research Activities (R&D credit) as an incentive to mitigate tariffs’ potential negative influence on innovation.

Current Tariff Environment

Toward the beginning of his term, President Trump invoked the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to levy 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico via executive orders in response to concerns over immigration and illegal drugs entering the United States. Shortly after, the president issued an executive order that imposed a 20% tariff on China in response to concerns over the opioid/fentanyl drug crisis. In April, President Trump enacted sweeping reciprocal tariffs that levied a baseline 10% tariff on all countries in a move to rectify the growing American trade deficit. In addition, the president issued additional tariffs on the automotive industry, aluminum, and steel. The Trump administration implemented each of these tariffs to advance a policy agenda (limiting drug traffic into the U.S.) or protect a particular industry (automotive and steel).

Shortly after implementing these tariffs, the White House issued an executive order granting a 90-day pause on the reciprocal tariffs except for those levied against China. Various countries including China and the U.K. came to the table to negotiate. The U.S. and China reached a tentative trade deal in which China removed the retaliatory tariffs and other trade barriers levied against the U.S. while keeping a baseline 10% tariff. In exchange, the U.S. suspended its 34% reciprocal tariffs against China while leaving a 10% duty and all fentanyl-related tariffs in place. China and the U.S. hammered out more details in an announcement later in June. According to the Trump administration, the U.S. will assess a 55% tariff on Chinese goods while China would levy 10% duty on American products. In addition, the U.S. provided concessions that reopened American universities to Chinese nationals. The Chinese promised to provide the U.S. with a supply of rare earth minerals and magnets. Both parties expect further negotiations to take place in the future.

This trade deal came on the heels of a trade deal between the U.S. and the U.K. that leaves the 10% reciprocal tariff levied against the U.K. in effect after the 90-day pause while adjusting the tariffs on aluminum, steel, automobiles, and automobile parts. In return, the U.S. receives trade concessions related to beef and ethanol. Forvis Mazars discusses this trade deal in more detail here.

The U.S. Court of International Trade (CIT) and the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia issued temporary blocks on the reciprocal and fentanyl-related tariffs. The Trump administration quickly appealed the CIT decision in the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals which granted a stay on the tariffs until it could hear arguments. The District Court’s decision remains in effect and continues to block reciprocal and fentanyl-related tariffs. See the Alert published by Forvis Mazars to learn more.

Forvis Mazars Insight: Forvis Mazars has published a variety of resources to navigate the current tariff environment. Please visit our FORsightsTM page for various articles on tariffs.

Impact of Tariffs on Innovation

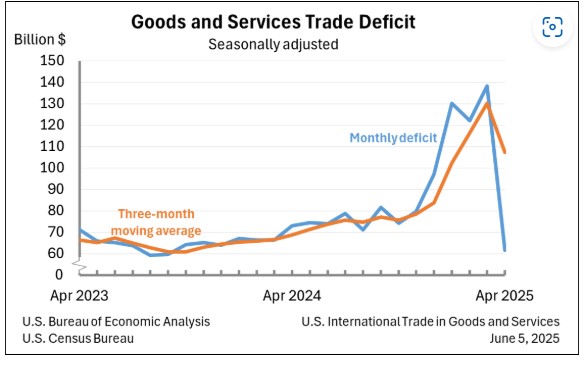

While the jury is still out on the potential impact of the recent tariffs, short-term economic results and a wealth of economic literature provide a glimpse into the overall impact of tariffs. In the short run, tariffs achieved their stated purpose: address the federal trade deficit. According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the federal deficit dramatically fell 55% as illustrated by Figure 1.1

Figure 1: Federal Trade Deficit2

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

Furthermore, imports decreased by 16% and exports increased by 3% from March 2025 to April 2025.3 According to an estimate by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the Trump administration tariffs would reduce the overall federal deficit by $3 trillion over a 10-year period and increase revenues from taxation which would lessen federal borrowing and burgeon funds available for private investment. These benefits spring forth as tariffs reallocate profits and jobs from foreign competitors to domestic firms according to economists.4

More tangible short-term benefits related to tariffs stem from their usage in trade negotiations. In aftermath of Trump announcing various tariffs, multiple countries sidled up to the negotiation table to work out a trade deal. As stated earlier in the article, the U.K. and China reached trade deals with the U.S. shortly after the U.S. announced sweeping reciprocal tariffs against all their trading partners. On top of this, a trade deal is expected between the U.S. and Canada in the coming weeks.5 The primary reason these countries are coming to the table appears to be correlated to the U.S.’ use of tariffs.

Additional short-term benefits ascribed to tariffs include improved national security and emerging industry incubation. As a classic example of tariffs used for national security, Adam Smith called for the use of tariffs to insulate particular industries vital for the “defense of the country.”6 To his logic, tariffs can insulate particular industries from foreign competition so they can develop and reduce dependency on foreign powers for important goods. In the modern realm, governments can employ tariffs to bolster national security by pressuring governments to keep certain goods from entering domestic borders. For example, the Trump administration utilized tariffs on China to pressure the country to restrict “fentanyl precursors” from entering the United States.7 These tariffs caused the Chinese government to tighten controls on fentanyl-precursor ingredients that U.S. did not want to enter its borders. As illustrated by these events, tariffs can bring some tangible short-term benefits in addition to the macroeconomic benefits described earlier in the article.

Some economists claim that these short-term benefits related to profit allocation, deficit reduction, and national security derived from President Trump’s tariffs are likely a short-term mirage.8 They predict that tariffs may cause a global trade disruption that may pass along higher prices to consumers. Higher prices diminish consumer purchasing power and increase inflation according to a CBO report. Each of these scenarios precede decreases in quality of life as goods and services become more expensive, and these prices are passed to consumers. Economists also project a corresponding decrease in gross domestic product (GDP) ranging from -0.61% to -3.61% resulting from widespread tariffs.9

Historically, reduced competition flowing from protectionist policies have diminished companies’ incentives to innovate. In a study looking at tariff cuts in the 1990s, economists found that for every percentage point cut in tariffs there is a corresponding 2 to 3% increase in innovation (measured by patent applications).10 In another study modeling the effects on tariffs on innovation, researchers discovered that “greater competition induced by lower trade barriers can lead firms to increase innovation rather than reduce it.”11 By putting up barriers to trade, countries remove foreign competition from the domestic markets which removes incentives for domestic firms to innovate and develop new goods and services that may better people’s lives.12 A decrease in the production of new or improved goods and services typically precedes a dip in welfare (an economic proxy for societal living standards). Innovation, in turn, plays a crucial role in enhancing society's standard of living.13 As such, some economists claim that failing to incentivize innovation through a subsidy like the Reagan administration’s R&D credit or increased access to global markets via free trade, leads to substantial innovation and welfare losses in the long run.14

Forvis Mazars Insight: According to economists, tariffs may produce short-term benefits and generate long-term consequences. Other incentives are needed to spur innovation and domestic manufacturing.

History of the R&D Credit

In 1981, the Reagan administration faced comparable questions to those faced by the Trump administration regarding concerns over the competitiveness of U.S. firms on the global stage in relation to trade and innovation. The Reagan administration pondered if the government should enact sweeping tariffs to counteract Japanese, German, and French advances in innovation or if the government should pursue an alternative action. Tariffs threatened to stifle economic growth in the long term but also promised to be an effective mechanism to immediately protect American businesses. The Reagan administration followed a different path that avoided the negative effects of a potential trade war. The administration championed and enacted a tax credit aimed at incentivizing research and development domestically under the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981. This gave birth to the R&D tax credit.

In its current form, the credit incentivizes R&D by providing a dollar-for-dollar reduction in tax liability for firms conducting qualified research. The credit is computed by comparing current year spend in pursuit of qualified research to a base period and multiplying the difference by an applicable rate. Under Section 41 of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC), the IRS defines qualified research as activities that seek to develop new or improved products or processes, are technological in nature, and undergo a process of experimentation to resolve technological uncertainties present at the outset of the project. Taxpayers quantify R&D expenditures by identifying costs related to these qualified activities. These expenditures include employee wages, supplies consumed in the R&D process, contract research payments, and computer rental payments. Once the dust on the calculation settles, the R&D credit generates around 10% return on investment for every qualified dollar spent on R&D. The federal credit also contains provisions to allow a payroll tax offset for eligible start-up businesses. In addition to the federal credit, various states utilize an R&D credit to offset state tax liability with varying rates of return for every dollar spent. In doing so, the R&D credit subsidizes innovation and improves business financial health. As such, the R&D credit remains a popular incentive for businesses in the U.S. to conduct R&D due to the many ways that taxpayers can wield R&D credits to reduce tax liability and improve the bottom line.

Impact of the R&D Credit

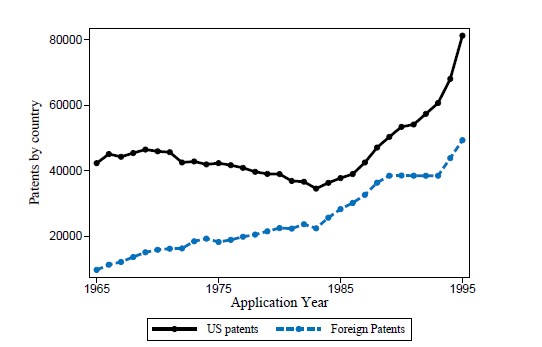

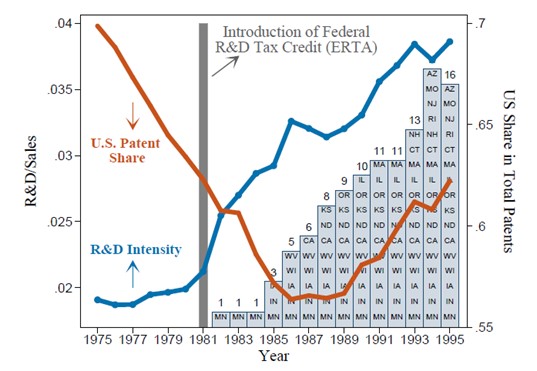

Since its inception in the U.S., the R&D credit sparked an increase in U.S. corporate leadership and technological prowess without incurring the potential negative impacts of tariffs. Economists illustrate this by comparing U.S. and foreign patent output from 1965 to 1995. In Figure 2, U.S. and foreign patents converge from 1965 to 1980 indicating a foreign “catch up” effect in which foreign innovation and technology capabilities began to converge with the U.S. capabilities.15 In addition, from 1965 to 1980, the U.S. patent rate fell in a downward trend, likely indicting a reduction in R&D intensity. In other words, the American innovation and technological engine was sputtering. In 1981, the U.S. introduced the R&D credit, and the trend reversed. Patents in the U.S. increased at a dramatic rate and the gap between U.S. and foreign patents widened. In other words, the introduction of the R&D credit significantly increased U.S. research and innovation and the competitiveness of U.S. firms abroad. Figure 3 highlights the impact of the R&D credit below through the lens of patent share and R&D intensity. According to the economists compiling the data behind each of these figures, the R&D credit left a positive imprint on U.S. innovation without the potential negative effects that could be caused by tariffs.

Figure 2: Patent Counts16

Source: Akcigit et al (2018)

Figure 3: R&D Intensity and Patent Share17

Source: Akcigit et al (2018)

In addition to increasing R&D intensity and technological leadership for U.S. firms, the credit minimizes the cost of R&D which stimulates productivity. Tariffs often stagnate these improvements by increasing the costs of innovation and removing the incentives to compete. In other words, maximizing innovation appears to be contingent on a liberal, free trade policy.

As illustrated by economists, the R&D credit may serve as an attractive offset or policy alternative to a protectionist trade policy. While tariffs increase the cost of doing business, the R&D credit subsidizes production and innovation through the reduction of tax liability. In light of this, the R&D credit can be utilized as a mechanism to offset the costs of tariffs and increase innovation domestically.

Forvis Mazars Insight: The R&D credit can generate a 10% ROI on average for every qualified dollar spent and is an effective stimulant to innovation without the potential negative effects of tariffs.

Limits on the Effectiveness of the R&D Credit

While the R&D credit proves to be a lucrative incentive for businesses, the credit has had its drawbacks. The TCJA, under IRC Section 174, required businesses to capitalize domestic and foreign research and experimental expenditures (REEs) over a five- and fifteen-year period respectively rather than expensing these expenditures immediately. This dramatically increased tax liability for taxpayers conducting R&D and disincentivized performing these activities. In a 2018 report, the CBO estimated that the effective tax rate (ETR) on R&D was -14% before the capitalization rules came into effect. This negative effective tax rate indicates that the tax code was subsidizing R&D. After the capitalization rules came into effect, the ETR swung to 11%. This swing in ETR indicated that the tax code is no longer subsidizing R&D but penalizing it. A report developed by the Congressional Research Service (CRS) drives this point home by reporting that the cost of capital investments in R&D increased by 1.8% after the implementation of REE capitalization rules. Economic analysis shows that the capitalization requirements ultimately tempered the effects of the R&D credit by rendering R&D more expensive. The Trump administrations passed House Resolution 1 (the Act) which restored domestic expensing of REEs and continued capitalization requirements for foreign REEs. In doing so, the Act incentives domestic research and development by allowing immediate deductions for domestic REEs and penalizing foreign REEs. For more information on the Act’s provisions related to R&D, access this FORsight.

In addition to the capitalization requirements for REEs, the Form 6765, which is the form that taxpayers use to report the R&D credit, is undergoing some changes per the updated Instructions. Starting in 2024, taxpayers will have to report the total number of business components making up their current year qualified research expenditures (QREs), enter the amount of officer wages included in QREs, disclose any acquisitions or disposition of a trade or business during the year, highlight new categories of QREs, and divulge if the taxpayer utilized ASC 730 to compute their QREs. In 2025, the list goes into more depth. The IRS mandates that taxpayers disclose all QRE categories (wages, supplies, contract research expenditures, and computer rental expenses) broken out by business component and by project, release qualitative information for each business component, and break out wage QREs by activity category. These information requests dramatically increase the quantity of information required and the level of effort required by the taxpayer to complete the calculation.

How Forvis Mazars Can Help

The landscape surrounding the credit and tariffs is complex. With changes coming to the R&D credit and the evolving tariff landscape, a trusted advisor is needed. Our national team at Forvis Mazars has significant experience assisting clients with R&D credit calculations for a vast portfolio of businesses and industries. To take advantage of the R&D credit or evaluate whether this could be a viable solution for your business, please reach out to our R&D credit practice to learn more. For assistance related to navigating tariffs, please contact a professional at Forvis Mazars here.

- 1“US International Trade in Goods and Services, April 2025,” bea.gov, June 5, 2025

- 2Ibid.

- 3Ibid.

- 4Akcigitet al (2018). “Innovation and Trade Policy in a Globalized Word.” International Finance Discussion Papers 1230. https://doi.org/10.17016/IFDP.2018.1230

- 5“Carney Says Canada and US Aiming for Trade Deal Within 30 Days,” bloomberglaw.com, June 16, 2025

- 6Smith, Adam (2012). “An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations.”

- 7“China Tightens Controls on Fentanyl But Calls It a US Problem,” nytimes.com, June 25, 2025.

- 8Akcigitet al (2018). “Innovation and Trade Policy in a Globalized Word.” International Finance Discussion Papers 1230. https://doi.org/10.17016/IFDP.2018.1230

- 9“How Will Trump Tariffs Impact the US Economy,” taxfoundation.org, November 8, 2024

- 10Coelli et al (2022). “Better, Faster, Stronger: Global Innovation and Trade Liberalization.” The Review of Economics and Statistics Vol CIV.

- 11Lim et al (2018). “Trade and Innovation: The Role of Scale and Competition Effects

- 12“How Protectionism Poisons Innovation,” chicagobooth.edu, September 24, 2018.

- 13“20 Ways Business Drives Innovation and Improves Lives,” uschamber.com, January 25, 2024.

- 14Akcigitet al (2018). “Innovation and Trade Policy in a Globalized Word.” International Finance Discussion Papers 1230. https://doi.org/10.17016/IFDP.2018.1230

- 15Ibid.

- 16Akcigitet al (2018). “Innovation and Trade Policy in a Globalized Word.” International Finance Discussion Papers 1230. https://doi.org/10.17016/IFDP.2018.1230

- 17Ibid.