Introduction

The higher education industry is at the end of the long corridor called the COVID-19 global pandemic. Let us reflect on what we observed. We will start by looking at the current pace of change today, the recent prognostications about the health of the higher education industry, and the road ahead … should institutions punt? Surge forward? Or opt for the status quo?

The Current Pace of Change

Looking back over the last three fiscal years (FY 2020, 2021, and 2022), industry observers who maintain a presence in the higher education community realize what a remarkable time it has been. Forvis Mazars’ observations and dialog from work with hundreds of colleges and universities give us great hope that innovation will continue at a “just-in-time” pace. Innovation and significant change happened at the outset of the pandemic when it was needed. Most feel they might have done things a bit differently, but the consensus seems to be most were, for the most part, able to make mid-course corrections faster than anyone thought possible.

This speaks to the resiliency and creativity of those who deliver higher education and those who lead and govern institutions of higher learning.

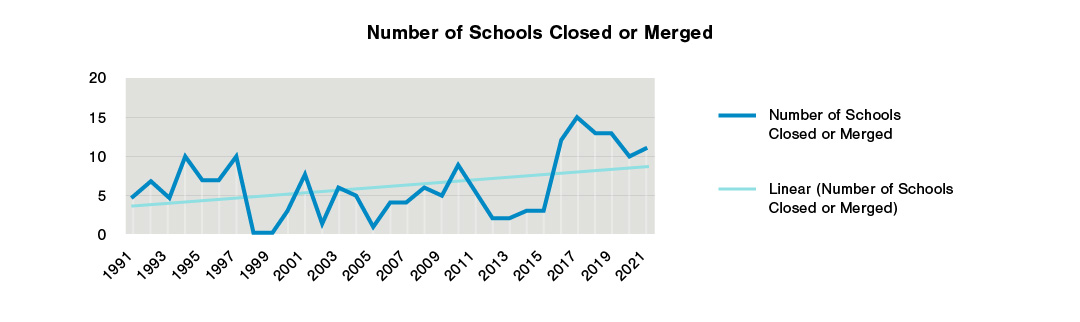

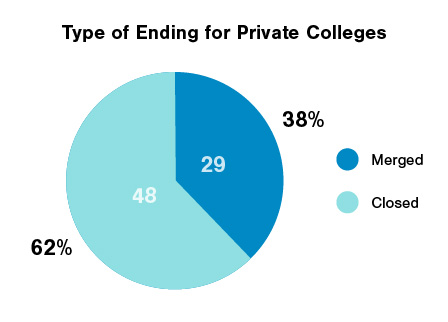

Looking at the data on college closures, one becomes aware of the increasing rise in the rate of closures from 2016 to 2021. Equally obvious is the increase of more mergers, consolidations, and collaborations than the past.

If one adds in the merger activity at public universities (states of Maine, Vermont, Georgia, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania), over the same 30-year period, you understand the rate of merger or consolidation industrywide is significant.

Prognostications: What’s Right & What’s Wrong About Them?

Predictions about the future of higher education are numerous and varied. They include reasoned estimates of the potential for increased closure rates like those predicted by Moody’s Investors Service.

In 2015, Moody’s Investors Service predicted that the rate of closures would triple by 2017 from the existing 25-year average of five per year to an increased average of 15 per year.1

Notably, the 2017 closure number hit 15.

Predictions also included the famous assertion in 2013, then repeated in 2017 by the late Clayton Christenson (Harvard Business professor and consultant), that half of all American universities will close or go bankrupt within 10 to 15 years. In response to a question at a conference in 2017, he accelerated his timetable when he stated, “I bet it takes nine years rather than 10.”

Futurist Tom Frey asserted, “The future of education will revolve around hyper-individualized learning, self-paced, organically generated content that is modality diverse, and available on-demand 24/7. Any topic, anywhere, anytime ... it will be less dependent on teachers, less dependent on schools, and offer more personal control.”

In 1997, internationally recognized management consultant Peter Drucker famously speculated:

“Education. Now there’s a subject that interests everyone today. President Clinton says we should pump more money into the present educational establishment. The current setup is doomed, at least so far as higher education is concerned. Thirty years from now the big university campuses will be relics. Universities won’t survive…” 2

Now in 2022, we are only five years from Drucker’s 30-year prediction. Does anyone think the big university campuses will turn into relics in the next five years?

What is wrong here? The dire predictions do not seem to be playing out. At least not right now. Drucker’s prediction is only five years away and Christiansen only has six years left.

Over the last few years, the industry experienced a global pandemic that triggered unprecedented relief for all of education including colleges and universities. The multiple waves of federal funds, forgivable loans to some, and the Employee Retention Credits all buoyed sagging revenues for the last three fiscal years (FY 2020 to FY 2022). But that largess is largely a thing of the past. The “one-time” handouts are mostly done and the “enrollment cliff” still looms. Many schools are working hard to make sure future budgets can be balanced. Many are working to re-tool both academic revenue, academic spending, and administrative spending.

Forvis Mazars has worked with numerous schools and many are finding ways to adjust operating plans that focus on an economically sustainable model. Some have achieved significantly improved results. Others have achieved modest results. But all are better off having gone through the discipline of the adjustment exercise.

With efforts to right-size both administrative cost and academic program delivery cost, it is doubtful these institutions will be the doomed relics predicted earlier.

Moody’s Investor’s Service smartly summarized their process in predicting the economic future of their rated schools. Susan Fitzgerald, senior vice president in Moody’s higher-education practice, says the ratings agency “starts with a quantitative assessment of factors like operating revenue, liquidity, and investments.”

She explains further, “But there are multiple other credit considerations that are unique to each institution that provide that forward look, and the forward look is really in large part driven by management and governance,” she says. “That’s a much more qualitative assessment than any number or group of numbers will give you.” 3

No wonder Moody’s analysis and predictions about the outlook for higher education rated schools are usually right on target. It takes more than a few numbers to adequately predict the future economic life of a college or university. They are complex and can be driven by a limited number of qualitative factors.

The Road Ahead: Heave-Ho or Status Quo?

On the eve of the demographic cliff (identified in WICHE data and discussed by Social Science Professor Nathan Grawe as occurring in the year 2026), it feels somewhat premature to predict with certainty that financial health will prevail. We know from other analysis (Zemsky, et al. in “The College Stress Test”) that 10% of schools face substantial risk and 30% are bound to struggle. 4 The reality of what is ahead, as Moody’s analysts predict, is likely to be more tied to leadership and other qualitative factors.

Leadership engaged in the right set of practices given clear guardrails by board policy can accomplish much and provide a clear path forward even for schools with weaker quantitative “scores.”

What should they work on? Here is a list of key initiatives that can provide results:

Leadership-Oriented Initiatives

- It all starts with leadership from the board and president. Updating strategic initiatives considering current issues is the place to start, followed closely by the quantitative items below. What are your habits and practices to monitor program demand? Do you maintain policy guardrails (like a net income or margin requirement) that will encourage all leaders to make good choices about fiscal stability and academic quality? Are you actively assessing collaboration and/or merger ideas? The best merger and collaboration solutions come in times of financial stability rather than when a school is painted into a fiscal corner.

- Provide strong “in-demand” programs with adequate funding to keep them strong.

- Prevent mission creep by making sure only necessary programs are funded (even ones that are under-enrolled but deemed mission-critical).

- Be proactive in finding alternative revenue sources in academic programs and in the use of facilities and other assets such as intellectual capital. A growing number of schools have revenue committees at the administrative level, the board level, or both.

- Provide stretch goals for advancement of leaders. We are in the middle of a generational wealth shift that can be taken advantage of with the right emphasis and approach.

Quantitative-Oriented Initiatives

- Bend the administrative cost curve down. This may prove challenging in an inflationary environment.

- Bring academic program delivery cost in line to reduce unnecessary costs using program revenue and cost analysis.

- Rethink and reposition liquidity to help keep adequate funding available in the inevitable downcycles.

- Restructure debt when possible to free up capital.

- Forecast, measure results, and adjust. A good modeling tool will help. Good budgeting tools also help, but start with modeling to stay focused on the big picture.

Conclusion

We do not believe colleges and universities are doomed to fail in large numbers in a short period of time. There will continue to be closures, but that pace will likely be at about the same pace as the industry is currently experiencing (perhaps from 10 to 15 institutions per year), with more of them each year being mergers or acquisitions rather than closures. Good executive leadership and good governance will go a long way to creating positive momentum for many schools, even in the face of significant obstacles.

Nathan Grawe, in his recent work “The Agile College: How Institutions Successfully Navigate Demographic Changes” says it best:

“With student centered, mission-focused reform, institutions may emerge, not untouched by demographic change but reshaped into better, if sometimes leaner, versions of themselves, prepared to serve students for generations to come.” 5

Work hard to find economic sustainability. It is achievable. If you have questions about how to make that happen, please reach out to a professional at Forvis Mazars.

- 1September 28, 2015 Inside Higher Education reporting on Moody’s prediction of college closures. Article by Kellie Woodhouse, accessed on June 6, 2022 at https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/09/28/moodys-predicts-college-closures-triple-2017

- 2Seeing Things as They Really Are, Robert Lenzer and Stephen S. Johnson, March 10, 1997, Forbes magazine https://www.forbes.com/forbes/1997/0310/5905122a.html?sh=7095729924b9 Referring to an interview done with Peter Drucker

- 3As quoted in “The Oddsmakers of the College Deathwatch: A small Industry of Experts Armed With Data is Ready to Tell You if Your College Will Survive”, Chronicle of Higher Education, February 1, 2020, Scott Carlson

- 4The College Stress test, Robert Zemsky et al, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2020 P. 117

- 5The Agile College, Nathan D. Grawe, Johns Hopkins Press, 2021 P. 212